Endogenous Risk

Endogenous risk

The pedestrian Millennium Bridge, opened by Queen Elizabeth II on 10 June 2000, was the first new bridge to span the River Thames in London for a century. Thousands of people crowded on the bridge on the day of its opening, supposedly not a problem, as the bridge was designed to cope easily with such large numbers.

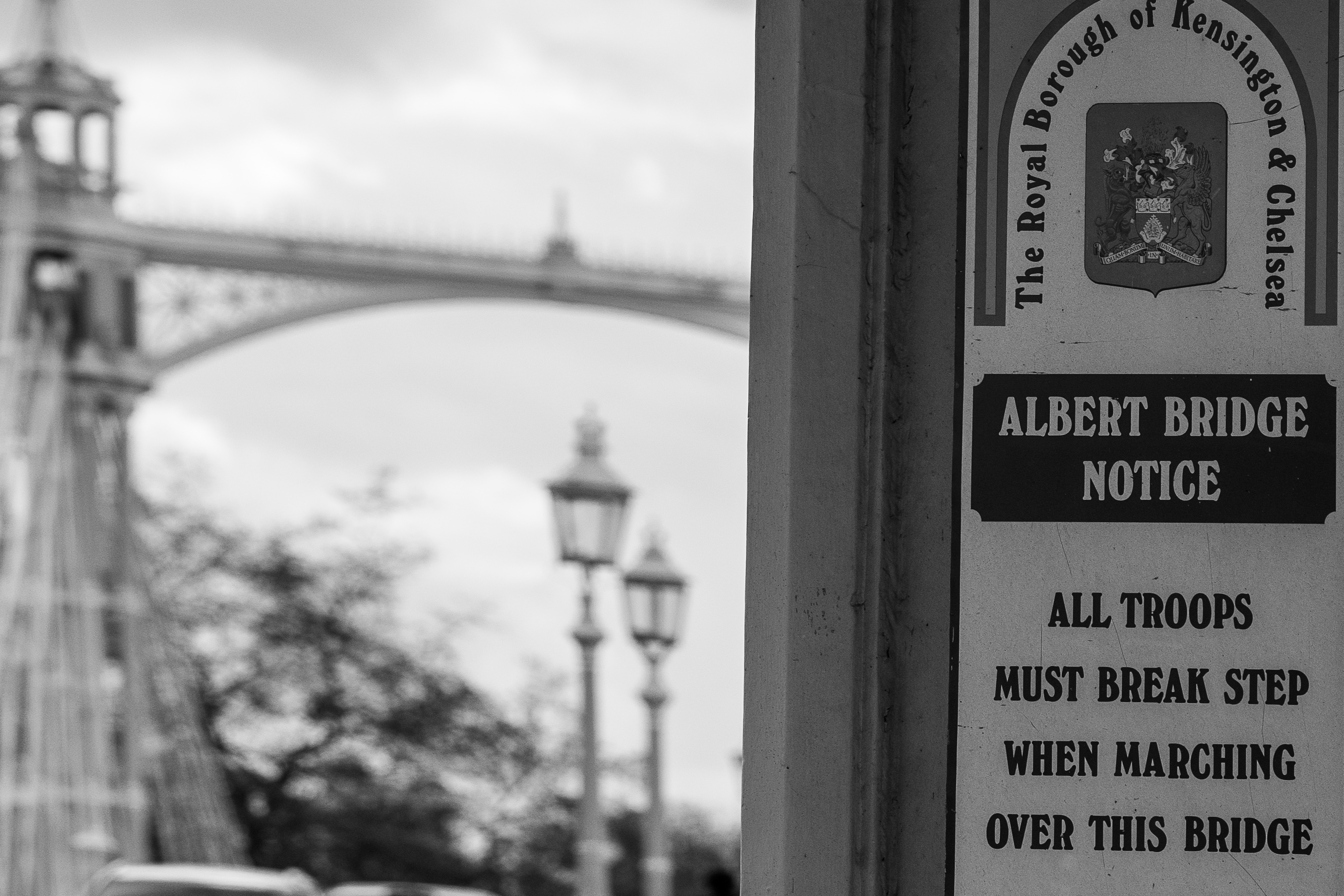

However, within moments of the bridge's opening, it began to wobble violently, to the great embarrassment of its designers — Arup Engineering and architect Norman Foster. In the process earning the nickname the "Wobbly Bridge." The swaying came as a surprise, as no such outcome had been predicted by Arup's extensive computer modeling and human testing. It is well known that soldiers marching across bridges can cause them to collapse; the reason why they are asked to break step when crossing bridges. Marching soldiers generate harmonized frequencies that can create feedback between the internal frequency of a bridge and soldiers' steps, leading to a collapse. If you look closely, you can often see signs on bridges telling soldiers to break step when marching, as the photo in the figure below I took of the Albert Bridge in London.

The problem caused by soldiers marching across bridges is, of course, well known, and Arup did consider that in their modeling. They even had a precise number; it would take 167 marching soldiers for the Millennium Bridge to wobble. But those crowding on the bridge on the opening day were not soldiers, but people from all walks of life, who, for most parts, did not know each other. The chance of them spontaneously marching was considered next to impossible.

But, the designers missed something important. Every bridge is designed to move with the elements, and the Millennium Bridge was supposed to sway gently in response to the Thames breeze. Soon after it opened, it was hit by a gust of wind, and moved sideways as expected. The pedestrians' natural reaction was to adjust their stance to regain balance — lean against the movement. Herein lies the problem. They pushed the bridge back, making it sway even more. As an ever increasing number of pedestrians tried not to fall, the bridge swayed more and more.

What happened was that when 167 pedestrians crowded on the bridge in windy conditions, a feedback loop emerged. It was always present, lurking in the background, but needed particular conditions to emerge.

It is the same in the financial system. The distinguishing feature of all serious financial crises is that they gather momentum from the endogenous responses of the market participants themselves, like a tropical storm over a warm sea gains more energy as it develops. As financial conditions worsen, the market's willingness to bear risk disappears because the market participants stop behaving independently and start acting as one. They should not do so, as there is little profit and a lot of risk in just following the crowd, but they can be forced to by circumstances.

So, how did Arup miss the potential for the Millennium Bridge wobbling? For the same reason, most financial regulations fail to prevent systemic risk. Arup modeled the impact of individual members of the crowd in isolation. But to properly understand the risk, it is necessary to study every aspect jointly: the weather, the bridge's mechanics, pedestrians' behavior, and the danger arising from individuals acting as one. All of these have to be studied simultaneously, or as we economists say it, in equilibrium. The Arup engineers knew about the danger arising from soldiers marching across the Millennium Bridge. They just never imagined a couple of hundred civilians not knowing each other would end up doing precisely that. Apparently, these feedback effects were known in some civil engineers' circles, but the natural instinct of companies to keep information proprietary meant it was not made public.

It took Arup 18 months to figure out what happened, and it eventually came up with two different solutions. They could either put a dampener on the bridge's movements or create noise — some mechanism that creates random movements to cancel out the synchronized swaying. Arup opted for the former, and it is working well. Still, the random noise solution would have been more interesting, at least from a financial system point of view.

There is a moral lesson in all of this. When something goes wrong, we always want to find someone to blame, someone to punish. On the Millennium Bridge, the natural self-preservation instinct of the people on the bridge caused the wobble — the precautionary principle. Nobody did anything wrong. They were just trying not to fall. Paradoxically, doing the right thing can bring about the worst possible outcome, and we often see that in crises. Market participants' self-preservation instinct causes liquidity to dry up in times of strain, taking us over the precipice into a full blown crisis. Who was to blame for the Millennium Bridges wobble? The engineers and the architects. Certainly not the pedestrians. Who is to blame for a financial crisis? It is not as clear cut, but the financial authorities who set the rules of the game do share the blame.

Endogenous and exogenous risk

Beauty contests were popular in British newspapers in the 1930s and they published pages of photographs of women, encouraging readers to vote for whom they thought prettiest. But there was a twist: A lottery ticket was given to those who voted with the majority. This inspired John Maynard Keynes when writing about how market prices are formed in his General Theory:

"It is not a case of choosing those [faces] which, to the best of one's judgment, are really the prettiest, nor even those which average opinion genuinely thinks the prettiest. We have reached the third degree where we devote our intelligences to anticipating what average opinion expects the average opinion to be. And there are some, I believe, who practice the fourth, fifth and higher degrees."

The readers did not choose their favorite based on who they thought the prettiest. They rather voted strategically to maximize the chance of voting with the majority and so get a lottery ticket. In the same way, speculators don't choose stocks based on the fundamentals of the company, they instead try to outthink other speculators.

Hyun Song Shin and I proposed a new direction for the literature on risk and uncertainty in 2002. We focused on the origin of risk and how the behavior of people leads to risky outcomes. In our view, risk can either be endogenous or exogenous.

A dictionary definition of the term endogenous refers to outcomes having an internal cause or origin. How an infectious disease spreads through a population is endogenous to the nature of that same population. If we always keep a safe distance between ourselves and our fellow countrymen, we will not get infected, but if we choose to live cheek by jowl with other people, our chance of infection is high. Your chance of getting a cold is endogenous to your behavior and those around you. One reason why taking the New York Subway can be hazardous to one's health. Why social distancing was so important in the Covid-19 crisis.

The opposite of endogenous is exogenous, where outcomes have an external cause or origin. When an asteroid hit the Gulf of Mexico 65 million years ago, wiping out the dinosaurs, that was an exogenous shock. There was certainly nothing the dinosaurs did that caused their demise. The risk of an asteroid hitting Wall Street as in the Figure at the top of this Chapter is exogenous.

Suppose I wake up this morning and see on the BBC website there is a 50% chance of rain. If I then decide to carry an umbrella when leaving my house, my doing so has no bearing on the probability of rain. The risk is exogenous.

Suppose, instead, I wake up this morning and see on the BBC website that there is some negative economic news about the United Kingdom, and in response, I decide to buy a put option on the pound sterling — I profit if the pound weakens. My actions make it more likely the pound will fall. Not by a lot, mind you, a tiny, tiny amount. But tiny is not zero — there is an endogenous effect.

I would not be doing anything wrong. On the contrary, I am behaving prudently, hedging risk, just like the pedestrians on the Millennium Bridge were trying not to fall over. Just like a single pedestrian on the Millennium Bridge did not make it wobble, me alone buying this put option will not make the pound sterling crash. Another ingredient is needed, some mechanism coordinating the actions of many people so when we act in as one in the market, our impact is strong. The chance of that happening is endogenous risk. All that is needed to turn some shock — the financial market version of the gust of wind hitting the Millennium Bridge — into a crisis is for a sufficient number of people to think like me (all wanting to prudently protect themselves) for the currency to crash. It is the self-preservation instinct of human beings that so often is the catalyst for crises.

No crisis is purely endogenous or exogenous, they always are a combination of an initial exogenous shock followed by an endogenous response. The same initial exogenous shock can one day whimper out into nothing, and the next blow up into a global crisis. When Covid-19 infected the first person in Wuhan, all the subsequent events could have been averted if that person had behaved differently. But nobody knew at the time. The reason why the exogenous shocks blow up into a crisis is that they prey on hidden vulnerabilities no one knows about until it is all too late. Social period.

The text in this blog comes from my book, Illusion of Control.