The dark side of well meaning rules and endogenous risk

Endogenous risk Regulations

The twin roles of market prices drive endogenous risk. The first is familiar, an idea fundamental to Friedrich Hayek's theories, that market prices embed all relevant information in the economy into one variable — the price. In a simple investment example often used in introductory undergraduate finance courses, the price of a stock is determined by the present discounted value of future dividends, where the discount factor embeds the uncertainty about the future.

Less familiar is the notion that prices are also an imperative to action, forcing us to behave in a particular way, perhaps even against our self-interest. This happens because most market participants are subject to a myriad of regulations, codes of conduct, and restrictions imposed by their trading partners and other stakeholders. These include accounting rules, legal obligations, disclosures, bank capital, risk constraints, and mark-to-market guidelines.

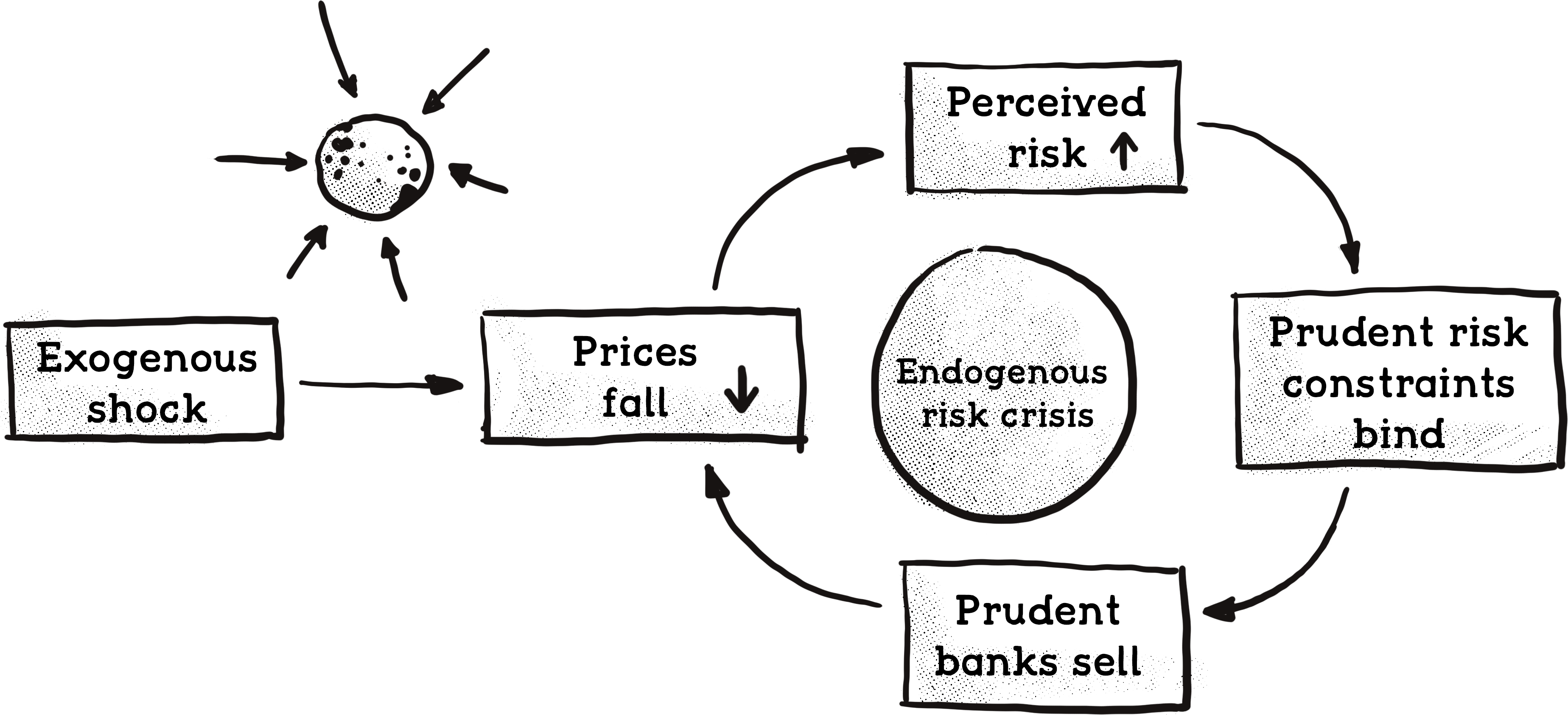

The consequence is illustrated in the figure. Suppose a bank holds some asset that falls in price by an unusually large amount. The measured risk of that asset will then increase and risk weights go up, so the bank's risk based capital ratio might fall dangerously close to the minimum set in regulations. To protect itself, the bank may have no recourse but to sell that asset. In other words, a change in prices causes riskometers to show higher risk, which in turn triggers forced selling, an example of how prices can be an imperative to action. That is exactly what happened in the Gamestop market turmoil in January 2021 when speculators fought each other, some shorting, others going long. Small speculators trading on the Robinhood platform were eventually unable to trade because Robinhood itself was forced to limit trading because it clears its trades via DTCC, and the heightened price volatility prompted DTCC to demand $3 billion in collateral from Robinhood.

A bank may not react to market outcomes in the way we expect it to because the constraints it is under dictate a certain type of behavior. If the bank is large, its trading activities will have a significant price impact. One could say that the presence of constraints undermines the integrity of the prices, taking them away from their fundamental values. In extreme cases, prices can become so distorted that they lead to undesirable extreme outcomes, like bubbles and crashes.

That said, these constraints don't bite all of the time, not even most of the time. It is only in times of stress that they significantly affect market prices. That observation goes a long way to explain why we decide to use riskometers and why they perform so poorly. The riskometers might describe the world quite well when everything is quiet but not capture behavior changes in times of stress. Why I called them fair weather instruments in the Illusion of Control.

What does this mean for regulations? That we should do away with all the rules and constraints? Far from it. The rules are by and and large very beneficial. Helping to keep the financial system orderly, protecting investors, and preventing abuse. However, they do have a dark side. Well meaning rules can act as a catalyst for making market participants act in unison, just like the Millennium Bridge's design made all the pedestrians march like soldiers. A good example is buying stocks on margin.

The first time stock markets became accessible to the general public was in 1920s America, as buying stocks was the preserve of the wealthy and connected before that. After World War I, anyone in America could buy stocks. Not only that, but they also didn't have to invest much money. One could bring $100, borrow $900 and buy $1,000 worth of stock — be leveraged nine times. This is called buying on the margin and became very popular. Money poured into the stock market, and since the U.S. was the only country where stock markets were open to the general public, money flowed to Wall Street from all over the world. The result was, of course, the mother of all stock market bubbles, one that came to a sticky end in September 1929, triggering the Great Depression.

The dark side of the well meaning margin rules shows its face when the bubble is bursting. Suppose I buy ten shares of IBM at $100 each, $1,000 in all. I put up 10%, or $100, of my own money and borrow $900. The entity financing this transaction will want some protection against the stock falling in price, insurance called a margin. Suppose the margin is equal to the initial $100. If IBM's price falls by 5% to $95, the investment is now only worth $950. I still owe $900, while my net value ($1,000-$950) has fallen to $50. However, the entity financing the transaction insists on 10% of the original amount, $100, so I have to make up the $50 shortfall. This is called a margin call, an immediate demand for $50. I have two choices: sell enough of the stock to pay back the borrowed funds or find $50 elsewhere. Many investors will have no choice — they can't find the $50 in time and have to sell some stock.

How likely is a day like that? I looked at the history of IBM stock prices and got 22,696 observations. Out of those, there are 117 days when the price of IBM fell by 5% or more, so the likelihood of a 5% price drop is 0.52% or about once every 9 1/2 months. If the price falls by 10% or more, we are wiped out; such days have happened 13 times, or almost one day out of every seven years.

Investors may have no choice but to sell the stock to meet the margin. Yet if a large number of investors are in the same situation, a significant volume of sells hit the markets simultaneously. Prices fall even more, creating yet more margin calls, more investors have no choice but to sell, and prices fall more. An endogenous risk vicious feedback loop emerges from the dark as in the figure above.

“[t]he conditions for the optimum of the individual are not the conditions for the optimum of the group.” Milton Friedman (1953

The text in this blog comes from my book, Illusion of Control.